Handle Internet-Scale Traffic

Reverse Proxy Caching — Don't Go Viral Without It.

Everyone using WordPress knows caching needs to be a part of their performance and scalability strategy, which is why there are several cache-oriented tools in the top 10 list of WordPress plugins, such as Batcache. A page caching plugin can mean the difference between weathering a traffic spike or going down in flames, but when the solution is driven via the app itself, serving repetitive traffic becomes the full-time job of the PHP Application servers, making it more difficult to scale.

The front page of a vanilla WordPress installation with one post requires billions of CPU instructions. Even with the fastest processors and the most highly optimized site, a caching approach that still requires loading the application on every request isn’t the optimal solution for scalability.

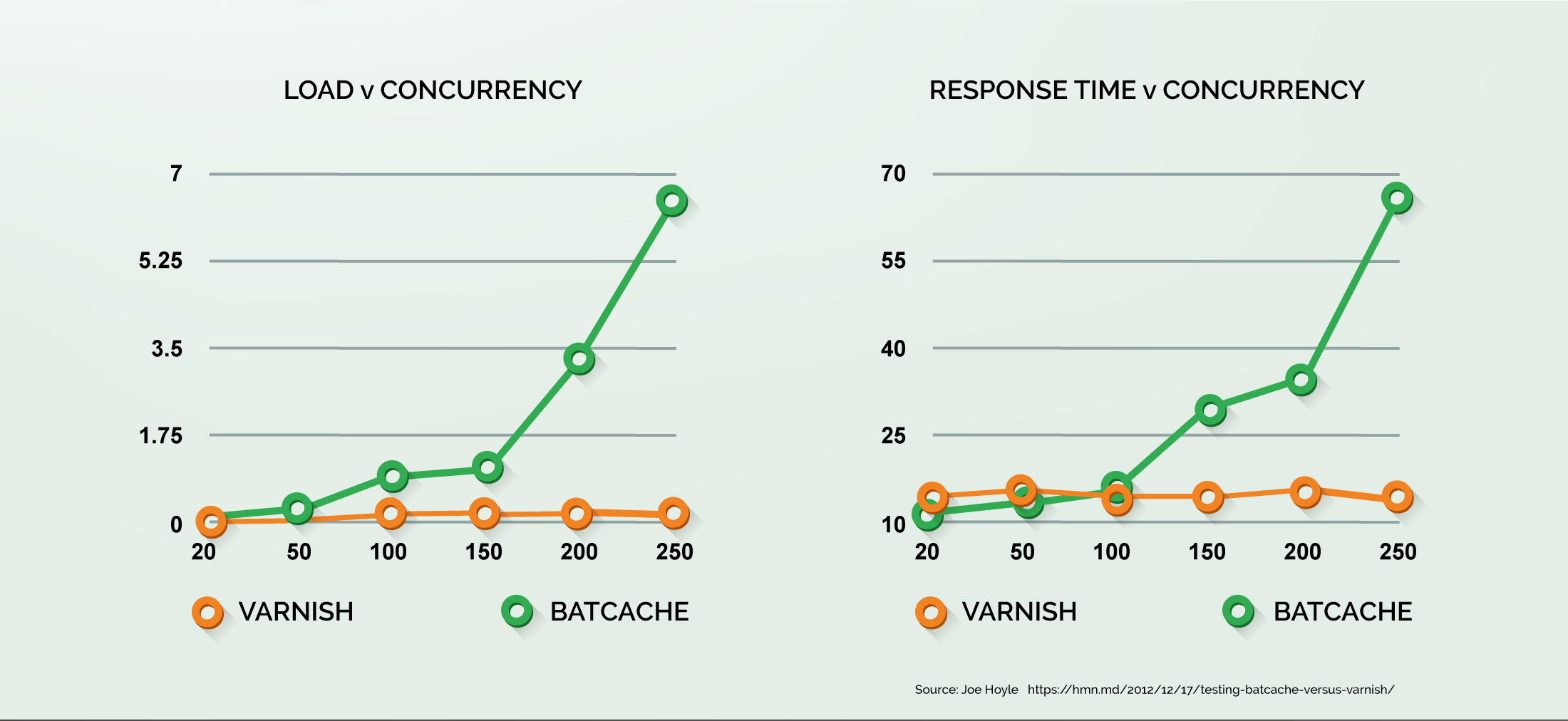

Take a look at these charts from Joe Hoyle at HumanMade comparing Batcache (which loads WordPress to serve its cache) to Varnish (which doesn’t touch WordPress at all):

As concurrency increases, Batcache’s response remain well within the realm of acceptable, under 1/10th of a second. However, a server load of 7 indicates that the application environment is pegged. The engine is redlining. While it’s nice that this flood of visitors are still seeing pages relatively quickly, good luck trying to do anything in the admin area (e.g. fix a crucial typo) with the server load that high.

The good news is that the wider open source community has been working on this problem since the early days of the internet, as it is a problem shared by every website and web application. There are well-established tools and patterns that can be put to use, which the WordPress community have adopted and integrated as best-practices. The answer for page caching with WordPress at scale is to use a reverse proxy.

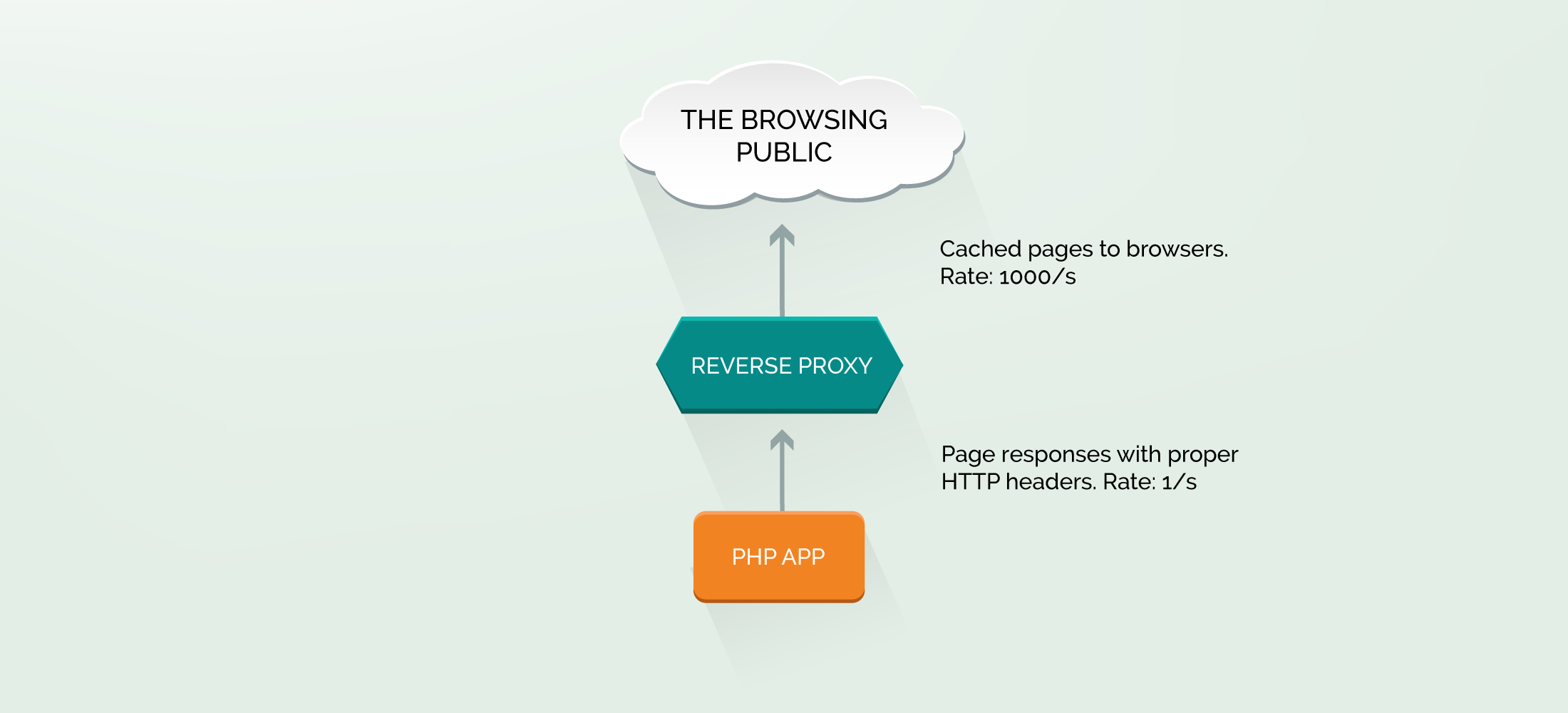

In this model, requests and responses to/from WordPress flow through an intermediary service known as a reverse proxy. The proxy can serve a cached copy of a response for a specified period of time. Caches can also be actively expired or flushed.

To put this in more concrete terms, consider a request from a visitor to your website’s homepage. On the very first request for the homepage, the reverse proxy doesn’t yet have a cached version of the homepage, so it passes the request back to WordPress. WordPress generates the homepage, and serves the response. The reverse proxy passes the response along, but also stores a version for itself. Then, on a subsequent visit to the homepage, the reverse proxy can serve the response without needing to connect to WordPress.

This model helps solve the challenge of scaling WordPress because a reverse proxy can be literally three orders of magnitude (1000x) more efficient than a PHP web server at delivering cached responses. PHP web servers need to perform a large number of relatively complex operations — connect to a database, execute thousands of lines of code, process business logic, etc. All a reverse proxy needs to do is serve a static value from cache.

The most popular open source reverse proxy is Varnish, but Nginx also has reverse proxy functionality and there are also hardware and commercial options available. In addition, some CDNs can act as massive distributed reverse proxies. Akamai, CloudFlare and Fastly are all excellent products for globally-distributed reverse proxy solutions. With these services, not only will your site scale for high traffic your site visitors will also get much faster responses because they'll be connecting to edge servers located near them as opposed to having to connect to the web servers in your data center.

Challenges:

- Cache TTL and Expiration: Initial communication between WordPress and the reverse proxy happens through the use of HTTP headers which can specify the lifetime, or Time To Live (“TTL”) of a cached page. However, actively expiring or flushing a cache requires additional work — you will have to devise a mechanism for clearing the cache that’s more sustainable than restarting the proxy.

- Cookies: Most Proxies rely heavily on browser-side characteristics — e.g. cookies — to decide whether a request can be given a cached response, or if it must be passed back to WordPress. If the reverse proxy, or WordPress, are improperly configured, then too many requests can be sent back to WordPress, which can drastically decrease the effectiveness of the proxy cache. This can present some challenges in a world where there are many different systems using Cookies differently.

- Complexity: For many developers, the conceptual complexity of introducing a new system, and not having the web-browser talk “directly” to WordPress, can create confusion around how to debug problems. Taking the time to ensure everyone on the team is comfortable with the implementation is important.

Further Reading

Common Pitfalls With Caching

Know the challenges and risks going into any performance optimization.

Nginx as a reverse-proxy for WordPress

Specific setup instructions for using Nginx as a reverse-proxy in front of WordPress

Varnish and WordPress

Step by step instructions to setting up Varnish in front of WordPress, from the makers of Varnish.